This past week I attended the annual meeting of “The Retina Society,” a collection of the brightest minds in the research and treatment of medical and surgical diseases of the retina and vitreous. Here are a few particular highlights of the meeting.

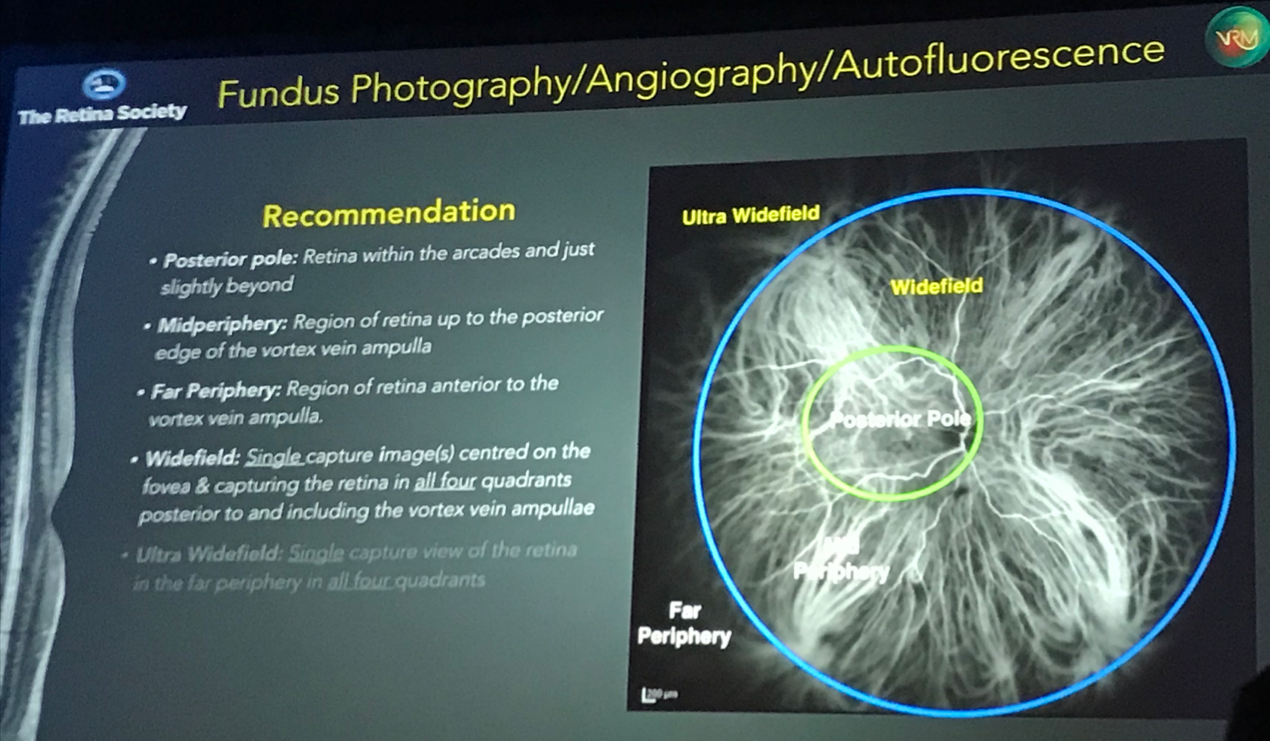

Classification & Guidelines for Wide-field Imaging: Recommendations from the International Wide-field Imaging Study Group

Netan Choudhry, MD, FRCSC gave an interesting presentation discussing the classification and guidelines for wide-field imaging, proposing recommendations from the International Wide-field Imaging Study Group on the nomenclature of imaging. He pointed out the various inconsistencies of fundus nomenclature, such as whether a photo taken by an Optos camera, is wide-field or ultra wide-field. Dr. Choudhry suggested that instead of characterizing photos by the degrees, i.e. asking a photographer to capture a 55 degree fluorescein angiogram, that the terminology used to describe photos incorporate anatomical landmarks within the retina, which better reflect an ophthalmologist’s clinical exam. Below is a photo from Dr. Choudhry’s talk, with his proposed anatomical landmarks to define wide-field imaging.

- Posterior pole: Retina within the arcades and just slightly beyond

- Midperiphery: Region of retina up to the posterior edge of the vortex vein ampulla

- Far periphery: Region of retina anterior to the vortex vein ampulla

- Widefield: Single capture image centered on the fovea and capturing the retina in all four quadrants posterior to and including the vortex vein ampullae

- Ultra widefield: Single capture view of the retina in the far periphery in all four quadrants

- Panretinal: 360 degree ora-to-ora view of the retina

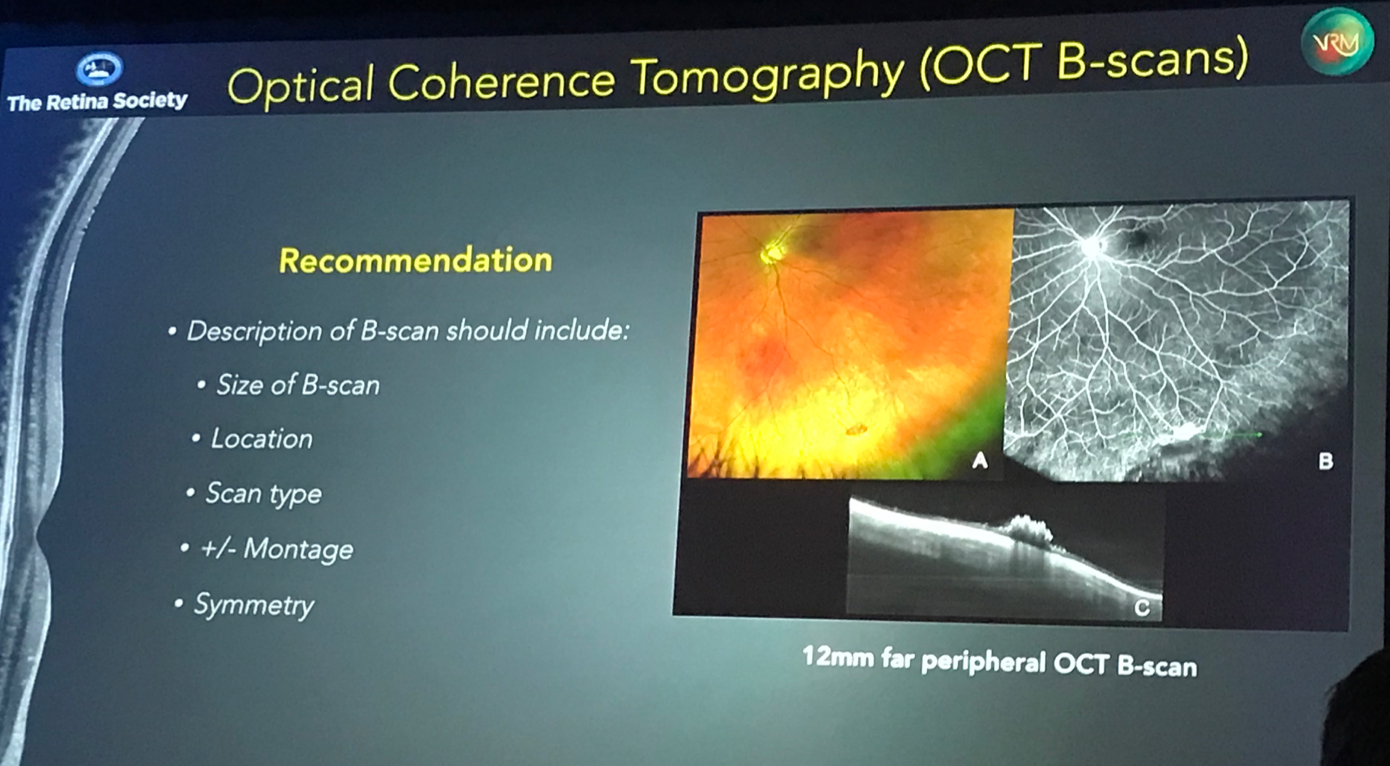

Choudhry also suggested that additional terms be given when defining OCT and OCT-A images, including the size of the scan, the location, the scan type, whether or not the scan is a montage compilation of individual scans, and describing the symmetry of the scan. As widefield and ultra widefield OCT become more readily available for clinical use, it will not be sufficient to simply state that one is looking at an “OCT of the right eye,” but that one should describe an OCT as being, for example, a 3 mm SD-OCT of the macula in the right eye, or a 12 mm far peripheral montage SD-OCT B-scan of the left eye.

As imaging technology continues to advance, we must become consistent in the descriptive terminology of what is being imaged. This comes into play in clinical documentation and research publications, but more commonly, at least in my experience, in resident teaching lectures, where trainees (often first-year ophthalmology residents) are asked to describe a fundus photo or an OCT. We must teach trainees to use a uniform set of descriptive terms to describe what they are seeing. I applaud Dr. Choudhry and his team for tackling this important subject, and encourage any trainee readers to begin using these recommendations when describing fundus and OCT images.

Detection of Retinal Detachment Complicating Degenerative Retinoschisis by Wide-field Fundus Autofluorescence Imaging

Jean Pierre Hubschman, MD gave a fantastic presentation describing the use of wide-field fundus autofluorescence for the detection of retinoschisis and retinal detachment. We often have the difficult challenge of determining whether a detachment is a retinal detachment (detachment of the neurosensory retina from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium), a cavity of retinoschisis (which is a separation, not detachment, of layers within the neurosensory retina), or a combined retinoschisis detachment where areas of elevated retina into the vitreous cavity have features of both retinal detachment and retinoschisis. OCT has become an extremely helpful tool in determining retinoschisis vs retinal detachment, but typical OCT imaging, is largely limited to the posterior pole, and these combined schisis detachments are often located more anteriorly and beyond the ability to easily obtain OCT images. We can now use wide field OCT imaging to characterize these lesions, but it would be nice to have additional, and in many cases, more readily available, tools to determine if an area of concern comprises retinoschisis, retinal detachment, or both.

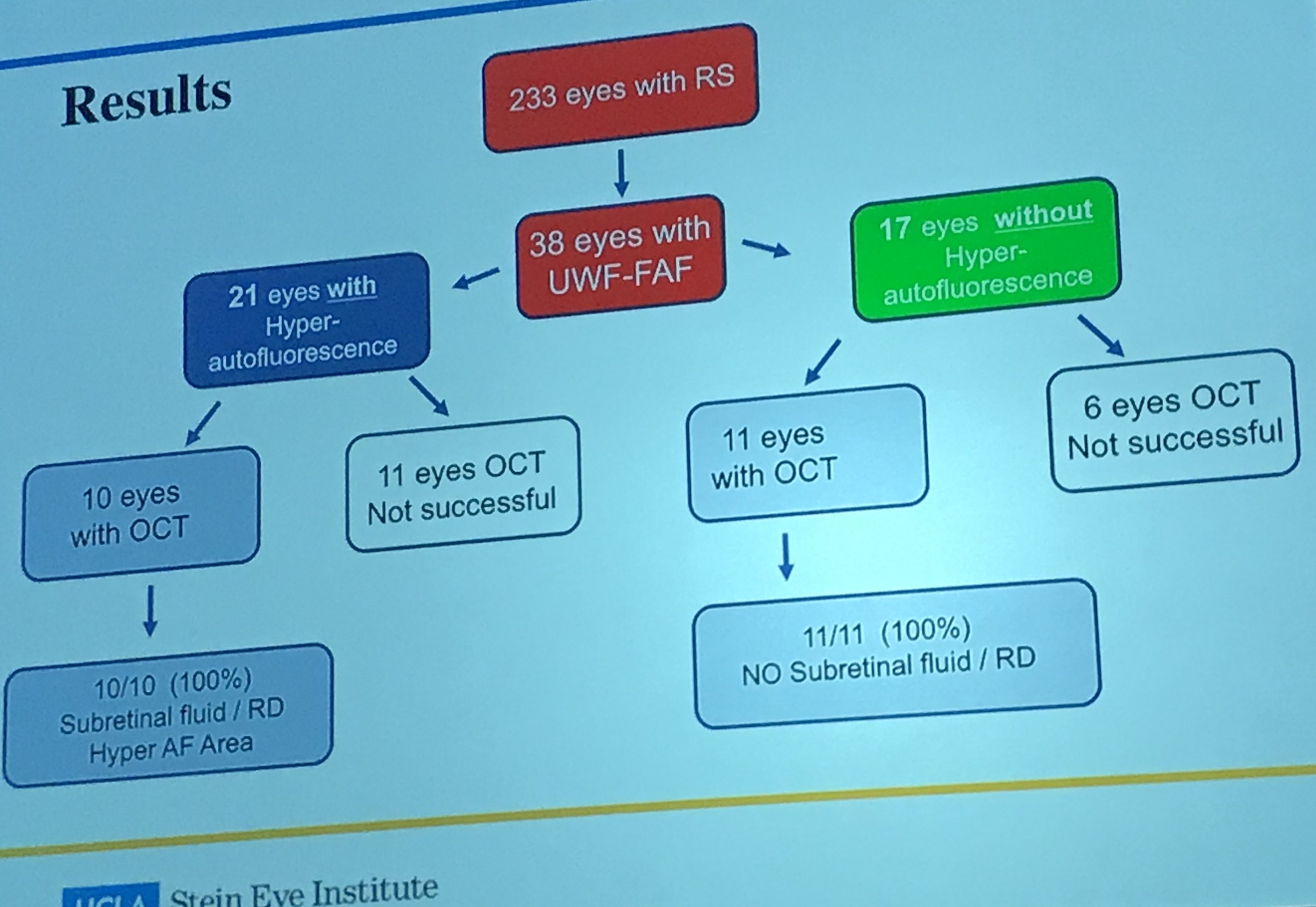

Dr. Hubschman study used wide field autofluorescence to characterize areas of retinal detachment vs retinoschisis, and used wide field OCT as the gold standard upon which to test autofluorescence accuracy. Dr. Hubschman analyzed retinoschisis eyes with hyperautofluorescence and those without hyperautofluorescence, and found that among 10 retinoschisis eyes with hyperautofluorescence (in whom OCT was successful), 10/10 (100%) had subretinal fluid characteristic of a retinal detachment. Among 11 eyes without hyperautofluorescnce and OCT, 11/11 (100%) did NOT have subretinal fluid and were thus characteristic of retinoschisis.

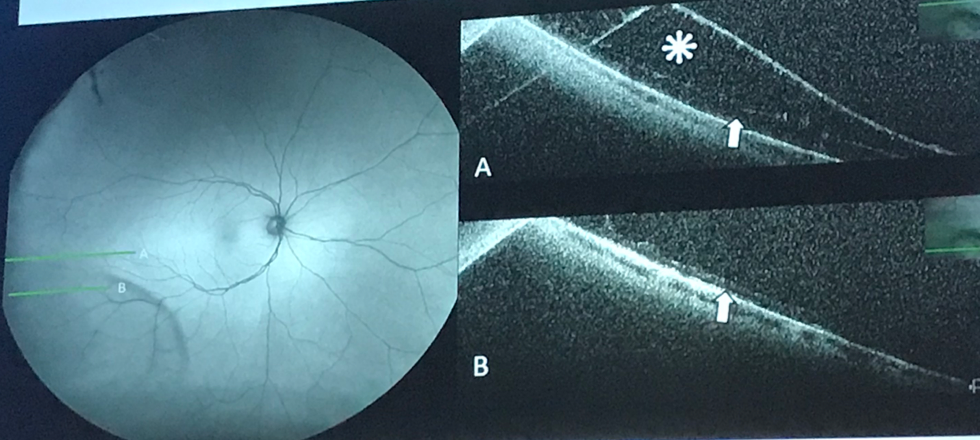

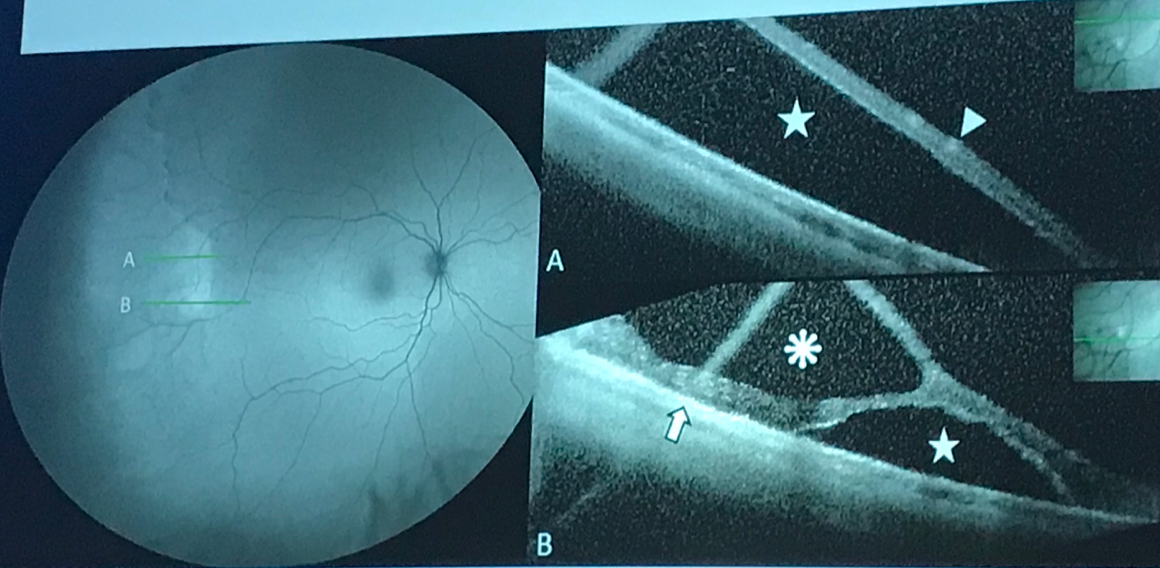

Take a look at a few of the photos below. Zones of increased autofluorescence in retinoschisis cases corresponded to areas of full-thickness neurosensory retinal detachment. This finding is extremely helpful in cases of combined retinoschisis/retinal detachment, where it can be difficult to determine the areas of true neurosensory detachment vs cavities of retinoschisis. Congratulations to Dr. Hubschman and his team for giving us another method for characterizing these clinically challenging retinal lesions.

Wide-field autofluorescence of a classically-located inferotemporal retinoschisis with notable hypoautofluorescence and corresponding peripheral OCT B-scans confirming retinoschisis. Photo cred: Jean-Pierre Hubschman, MD

Wide-field autofluorescence photo and corresponding SD-OCT scans corresponding to “A” and “B”. Notice that in “A,” where the OCT shows complete neurosensory retinal detachment, the lesion is fairly homogenously hypoautofluorescent, while in “B” there is a pocket of hyperautofluorescence corresponding to the area of retinal detachment and adjacent the hypoautofluorescent schisis cavity. Photo cred: Jean-Pierre Hubschman, MD

Pigmentary Maculopathy Associated with Chronic Exposure to Pentosan Polysulfate Sodium (Elmiron) for Interstitial Cystitis

Dr. Nieraj Jain gave an interesting talk describing (and alerting) retina colleagues to a new and possibly avoidable maculopathy associated with chronic exposure to pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS), the only oral medicine that is FDA approved to treat interstitial cystitis. No, interstitial cystitis is NOT a new variant of macular edema, interstitial cystitis is a type of chronic bladder pain you may remember hearing about in medical school, and is a type of chronic bladder pain causing urinary urgency and pain with intercourse. Dr. Jain recounted a recent patient seen in his clinic with findings consistent with pattern dystrophy but normal macular dystrophy genetic testing. He then recalled another prior patient with a similar clinical appearance and recognized that both patients had been on PPS for interstitial cystitis. He then queried his EHR patients on Elmiron, and found that out of the six patients that were on this medication, all six had maculopathies suggestive of pattern dystrophy, but without any family history of maculopathy or abnormalities on genetic macular dystrophy panels. Below is a picture from this case series, published in the May 2018 issue of Ophthalmology.

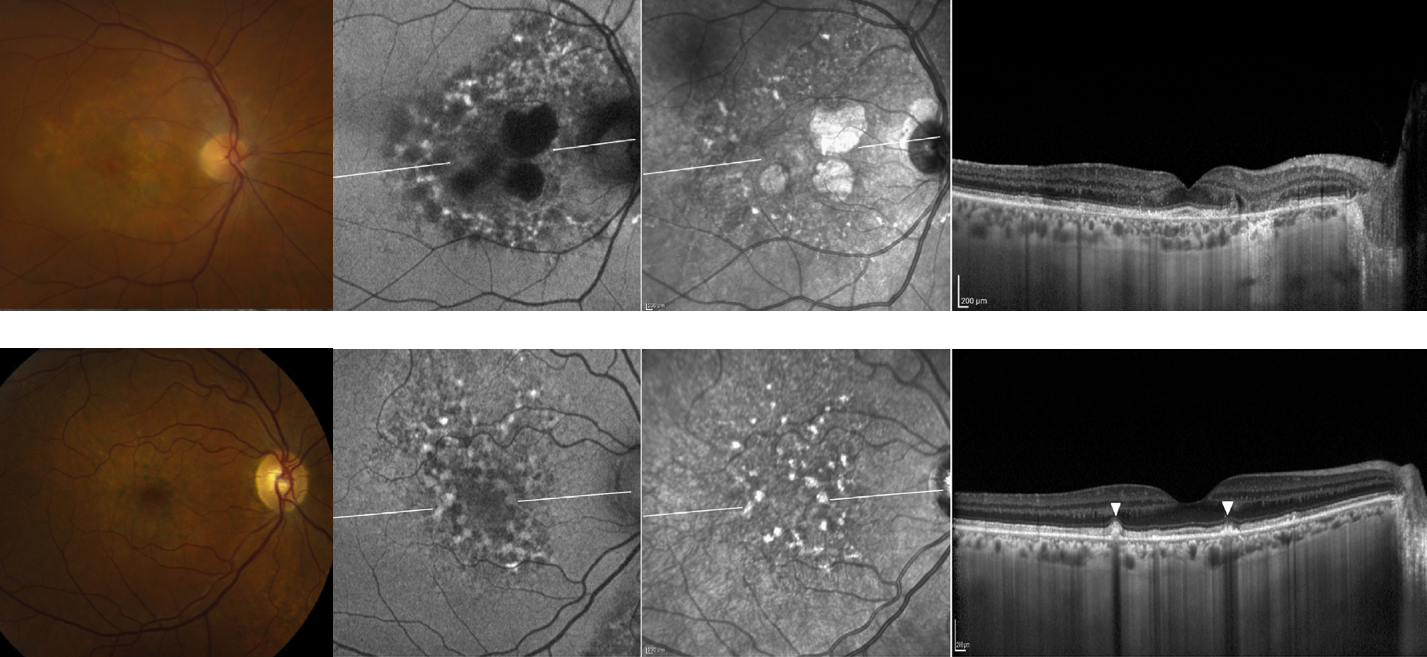

Color fundus photos (left column), autofluorescence, near-infrared photos, and foveal OCT B-scans from two patients at various levels of severity. In patient A (top row) notice the pigment atrophy, speckled hyperautofluorescence with patchy hypoautofluorescence, and corresponding areas of RPE atrophy. In patient B (bottom row) note the subtle parafoveal pigment deposits, speckled lesions as seen in patient A, and corresponding nodular excrescences at the level of the RPE. See Ophthalmology publication (link above) for full details.

While Dr. Jain was careful to definitively claim causality between this medication and the maculopathy, he did suggest that retina specialists, referring providers, and internists/urologists be aware of this potential association. Now here’s the exciting part. In order to “get the word out” to the urology community, Dr. Jain et al. sent a letter-to-the-editor of the journal, Urology. If you love letters to the editor (and their spirited responses) as much as I do, please check it out here. In their response which is not-yet-published-but-available-online, urologists Nickel and Moldwin propose a large-scale survey to better investigate this association, stating “it is our responsibility as a urology community treating patients with interstitial cystitis to determine whether this observation represents reality…” and go on to conclude, “We should not let this important observation be relegated to the dustbin of misleading urological associations without being sure it deserves to be there.” Check out a discussion of Jain’s article and Urology response in this interstitial cystitis-related blog. Well done to all – both to Dr. Jain for in making such a keen clinical observation and reporting this potential medication-related toxicity, and to urologists Nickel and Moldwin for their witty candor and call for future surveys and additional investigation. I hope they come through with their call for additional surveys and study before relegating this concerning finding to the urological dustbin.

Macular holes concurrent with retinal detachments in the Primary Retinal detachment Outcomes (PRO) Study

D. Wilkin Parke III, MD discussed macular holes concurrent with retinal detachments, as part of the Primary Retinal Detachment Outcomes study (PRO). In this subset of the study, researchers found that the 84% of these cases achieved successful single-surgery repair of the retinal detachment, with a 93% success rate of macular hole closure. Of the 44 cases examined, 24 were repaired via vitrectomy and 20 by vitrectomy with scleral buckle, with phakic status being present in 75% of PPV/SB cases, not unsurprisingly. The most interesting finding for me, personally, was that approximately half of all cases (24 cases, 53%) underwent internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling, while 47% did NOT undergo ILM peeling. Inasmuch as my experience to this point in fellowship has been that most vitreoretinal surgeons opt to peel ILM in the setting of combined MH/RRD, I would not have expected the frequency of non-peeling during MH/RRD cases to be so high! Even more surprisingly, to me at least, the success of macular hole closure was not significantly different between the two groups, with MH closure being achieved in 92% of cases where the ILM WAS peeled, and 95% of cases where the ILM was NOT peeled. These findings are very helpful for preoperative discussions with patients as well as intraoperative surgical decision making.

Modern Techniques & Indications for Scleral Buckling Surgery

William Ross, MD gave a fantastic talk describing his experience with the repair of 8903 rhegmatogenous retinal detachments using scleral buckling procedures over a 37 (!!!) year period. How neat it was to listen to a true “buckler” describe his technique for scleral buckles, as everyone seems to do this procedure with their own evolved technique. Suffice it to say, Dr. Ross has placed MANY scleral buckles, and he is a true believer in the procedure, often in cases where others may opt for a primary vitrectomy without scleral buckle. Interestingly, Dr. Ross does not tighten the band, which may be why he suggests his patients do not have post-operative pain or buckle-induced myopia.

Here is “The Buckler” William Ross’s Technique for Scleral Buckles (ok I may have made that name up, but I like it!)

- Local retrobulbar anesthesia

- 360 degree conjunctival peritomy

- Loop rectus muscles with 3-0 silk suture

- Indirect ophthalmoscopy to identify and mark all retinal tears

- Cryopexy of retinal breaks

- Place 5 mm band beneath recti muscles (he typically places a 240 band)

- Place one 5-0 nylon mattress suture(s) in two inferior quadrants, with anterior suture approximately 9 mm posterior to limbus and with sutures 7-8 mm apart

- Tie 5-0 nylon mattress suture in two inferior quadrants

- Perform first anterior chamber tap

- Place and tie 5-0 nylon suture(s) in two superior quadrants

- Place silicone sleeve to enclose (NOT TIGHTEN) 5 mm band to avoid myopia

- Perform second anterior chamber tap

- Remove 3-0 silk sutures

- Close Tenon’s capsule and conjunctiva with 7-0 vicryl or 6-0 plain gut

- Indirect ophthalmoscopy to check for central retinal artery pulsation

And here are Dr. Ross’s “Slam Dunk Indications for Scleral Buckling Phakic Patients Under Age 55 and Without PVR”

- Superior tear(s) not suitable for pneumatic retinopexy

- Failed pneumatic procedure

- Traumatic retinal dialysis

- Tears at border of lattice degeneration

- Inferior equatorial tear(s)

- Combined retinoschisis/retinal detachment

- High myopia with foveoschisis (for which he places a macular buckle)

Outcomes of Repair of Moderately Complex Phakic Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment: The PRO Study

Edwin Ryan, MD presented the “phakic” side of the Primary Retinal Detachment Outcome Study (PRO), which was then followed several talks later by results of the PRO study in pseudophakic patients. This was a retrospective study of retinal detachment repair at several highly-respective practices around the country, and in the portion of the study reported by Dr. Ryan, examined phakic patients with “moderately complex” retinal detachments. Exclusion criteria which may have favored choice of PPV, PPV/SB, or primary SB were applied in order to examine phakic detachments deemed moderately complex. These criteria thus excluded patients <40 (would favor SB), vitreous hemorrhage (would favor PPV), RD <3 clock hours (would favor PPV or SB), RD >9 clock hours (would favor PPV/SB), or eyes with grade C PVR, giant retinal tears, significant cataract >2+, or planned membrane peel. In other words (you’re wondering what’s left, right?), the inclusion criteria were RDs with >3 but <9 clock hours, without significant PVR/VH/GRT and over age 40. The authors found that among the 789 eligible eyes, 22% underwent SB, 36% PPV, and 42% PPV/SB procedures, with the single surgery anatomic success rate being 91% for SB, 84% for PPV, and 91% for combined PPV/SB procedures. Did you notice that the single surgery success rate was similar for SB and PPV/SB procedures and these procedures had a higher chance of single surgery success? This is an important finding (hence the repetition here), as PPV alone was inferior (p<0.01) to SB and PPV/SB for primary repair in moderately complex phakic retinal detachments. The bottom line: phakic patients with moderately complex retinal detachments do better with SB or PPV/SB than PPV alone.

Relative Success of Current Techniques To Repair Primary Pseudophakic Retinal Detachments: The PRO Study

Daniel Joseph, MD PhD presented the “pseudophakic” side of the PRO study, though his side of the story did NOT apply the same exclusion criteria for moderate complexity as did that just described by Dr. Ryan. The findings described by Dr. Joseph, at least for me personally, the most shocking of all, and I wonder if you will agree. This study evaluated outcomes of primary pseudophakic rhegmatogenous retinal detachments treated with either PPV or PPV/SB. Among the 2094 eyes in the PRO study, 1150 were pseudophakic, and only eyes with PVR, <90 days follow-up, or prior glaucoma surgery were excluded, achieving a cohort of 887 eligible pseudophakic RDs. Not suprisingly, the majority (77%) underwent repair via PPV, with 23% undergoing PPV/SB. The real shocker was that the rate of single surgery anatomic success was different between the type of surgery performed (p=0.0046). Let me explain. Among eyes with mac-on RDs, single-surgery anatomic success was achieved in 87.8% of eyes treated with PPV alone, compared to 97.5% of eyes treated with combined PPV/SB. Similarly, among eyes with macula-off RD, single surgery anatomic success was attained in 80.7% of eyes treated with PPV alone, compared to 89.2% of those treated with PPV/SB. Wait, did you catch that? Three out of four pseudophakic RDs (without PVR or prior glaucoma surgery) underwent PPV alone, even though the rate of single-surgery anatomic success is roughly 10% lower for PPV alone when compared to combined PPV/SB. Is anyone else seeing this? Are we looking the other way at this data, or do we actually believe these findings? If we do believe it, then shouldn’t we be performing combined PPV/SB for pseudophakic RDs far more often than we are performing PPV alone? I am excited to talk to colleagues about this study, and to see if these results from the PRO study will change their treatment paradigm moving forward. Certainly other patient and surgeon factors contribute to a surgeon’s choice of a PPV alone instead of a PPV/SB, including discomfort of scleral buckling, induced myopia, etc., but hopefully this study will at least get people talking. I’m interested to read your thoughts about this study and whether it will change your surgical decision making.

Final thoughts

I really enjoyed attending the 2018 meeting of The Retina Society. The planning, presentations, and meeting experience were top-notch. While I didn’t present anything at the meeting this year, I loved attending as a fellow, and enjoyed learning from the incredible group of presenters and panelists. I would encourage any retina fellows reading this summary to apply for one of the fellows research awards (free travel, podium talk, and cash!), submit a poster, or just take advantage of the surprisingly affordable fellows registration rate to attend the meeting.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short summary of meeting highlights. I’ve done my best to summarize several of the best presentations so others not in attendance may also benefit and learn. Please let me know in the comments below if you appreciate this brief review and if you have any questions or thoughts on the presentations that I chose to highlight! What do you think? Will any of this change your management of patients in the future? I hope to hear from you!